[excerpted from, Stories Across Cultures: Europe, South & East, by Anne Hilty, ©2023]

My first visit to Cyprus began in the land of Aphrodite.

My latest: in the broken city of Famagusta. (But that’s another tale – to follow.)

Cyprus had loomed large throughout my life as one of the world’s hotspots for protracted, seemingly unresolvable conflict. (Korea, my first residence abroad, was another.) Already in progress since 1955, a major conflict took place in 1964 when I was just 1 year old, and others throughout the decade; in July 1974 when I was 10, a coup d’etat was attempted to annex Cyprus to Greece, Turkiye sent in troops – and the conflict entered a new phase.

And so, the Cyprus story was long familiar to me.

This was not the first conflict between Türkiye and Greece, however, with portions of the latter at various times part of the Ottoman Empire (now Turkish Republic), and the Greco-Turkish War from 1919 to 1922. Cyprus itself had been part of the Ottoman Empire, in fact, for 3 centuries, from 1571 until 1878 when the British took control, prior to which the island had been governed alternately by Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Romans, Arabs, and by Crusaders in tandem with the French.

The island was settled in the 2nd millennium BCE by Mycenaeans, however, primarily but not entirely Greek, who occupied a large swath of the region: most of today’s Greece, Macedonia, Thrace, Crete, multiple Aegean islands, and small settlements in today’s Italy, the Levant, and western Anatolia. This would indicate, then, a proto-Greek influence from the time of the island’s settlement.

An exceedingly complex culture, and politically complicated circumstance since mid-20th century (or perhaps, nearly all of its history).

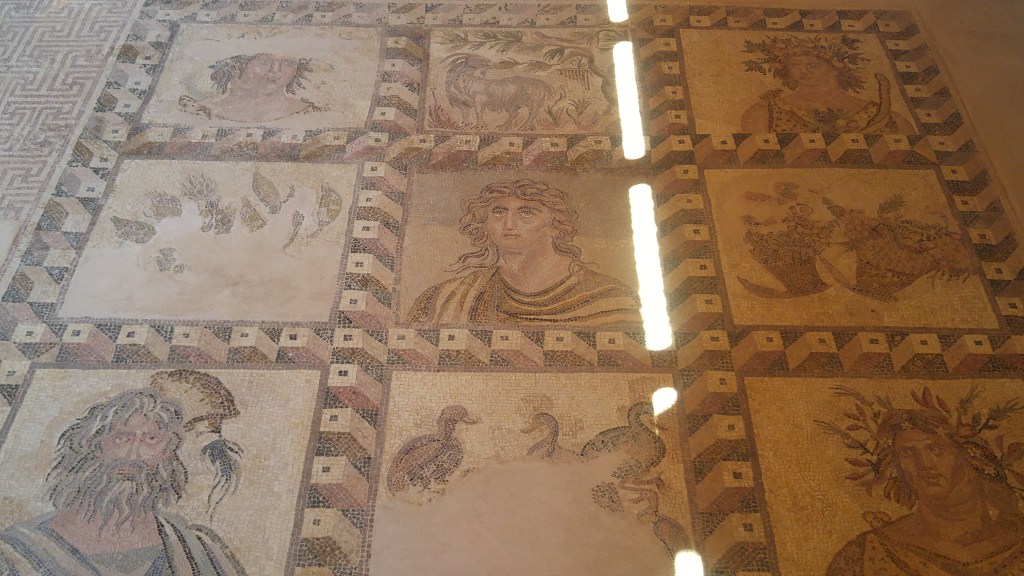

And so, in March of 2017, I made my first foray into this fascinating island, flying in from Athens to Paphos in the west – seen in Hellenic mythology as the birthplace of Aphrodite, goddess of love, beauty, fertility … and victory. As the island’s original capital, it was the center of her cult and she its patron goddess, while pre-Hellenic fertility deities were also associated with this region. The ancient site with its exquisite mosaics, near the waterfront, is UNESCO-inscripted as world cultural heritage.

I spent time not only here but also in Limassol, Larnaca, the capital of Nicosia, and then back to Paphos, thus crisscrossing the southern (republic, EU-member) half of the island with stunning views of the countryside. The island is exceedingly green, for a start, and the people’s relationship to the land pronounced. Filled with vineyards, lemon and olive groves, and formerly a major producer of carob, among others, the beauty cannot be adequately expressed. As a long-inhabited region, it’s also filled with archaeological sites and a mythology all its own.

In each of these I spent time with BPW colleagues, who had much to tell me about Cypriot culture – from the Greek-Cypriot perspective, of course. This is an island of many stories, often conflicting.

My Nicosia colleagues took me into the Old Town area to pedestrian Ledra Street with its UN-governed buffer zone and crossing point into Northern Cyprus, including plenty of fortification in the form of walls, barbed wire, and military patrol throughout the city. (I would cross over this border not 2 years later; see following story.) This was my stark introduction to the division of this island, including, following Germany’s 1990 reunification, the world’s only remaining divided capital – known also in ancient times as Lefkosia, and now Lefkoşa to the Turkish Cypriots on the other side of the wall.

My host in Nicosia had plenty to tell me about her family’s property in Famagusta’s seaside resort area of Varosha, until the 1950s one of the world’s playlands of the wealthy, now deteriorating all these years with no reciprocity. Following the August 1975 Voluntary Exchange of Populations Agreement, citizens of Turkish descent living in the south were required to move to the north and Greek Cypriots in the opposite direction; properties were abandoned, often with residence taken up by the incoming.

There is far more to this story, of course, but already well documented elsewhere. Suffice it to say, while some efforts for peace and cooperation between the two regions of Cyprus have been undertaken over the years, those in the south view this as illegal occupation (as does most of the international community) and, particularly those of older generations who had firsthand experience of the conflict, are consumed with resentment to this day. The wound is far from resolved.

I was to return to the island in January 2019, just in time for New Year’s Eve in Larnaca.

Flying in from Tunis this time, with a primary destination of Northern Cyprus, I landed on 31 December for brief visits to Larnaca, Limassol, and then up to Nicosia where I finally passed through that Ledra Street crossing on foot.

In Larnaca, having previously seen the 9th century Church of St. Lazarus, this time I explored the Hala Sultan Tekke complex (mosque, Sufi education center, cemetery), dating back to the 7th century while the complex was built sometime during the Ottoman Empire. This was a poignant reminder of the time when Greek and Turkish Cypriots lived comfortably together.

As the complex is along Larnaca’s large saltwater lake, I had a chance also to see the flamboyance of flamingos (yes, that’s the delightful group noun) that winter there each year.

Visiting Limassol once more, having toured the waterfront during my last visit I moved into its Old Town instead – largely closed during this first week of January between New Year’s and Orthodox Christmas. Ever so slightly eerie, and grand, to wander those typically busy streets alone.

In Nicosia this time, the Municipal Museum gave me a glimpse into the treasure trove of antiquity that is this island – an especially rich site of which, Salamis, is on the other side of that buffer zone, in the north.

Following a couple of weeks on the northern side of the island (see following story), I returned to the south by a then-new crossing between Famagusta and Larnaca (there are now fully 7 border crossings in Cyprus, several of which are pedestrian-only) and spent an afternoon in the resort town of Ayia Napa and its Pantachou Beach. Mostly closed in winter with few people, its multiple tavernas and shops nevertheless gave me an impression of its obvious carnival atmosphere in high summer.

Though a small island, there is always so much more to learn on, and about, Cyprus. As to the conflict itself, with its very many layers: a complex and possibly unresolvable circumstance indeed.