Greek is perhaps most celebrated for its islands. While popular vacation spots, each also represents a variant on Greek culture; it’s been said that there isn’t one Greek culture but many, with shared features but a good deal of distinction due to the country’s incredibly diverse landscape — with a certain measure of isolation as a result. Each island will at once feel familiar and yet with a culture of its own, creating endless opportunity for discovery.

Santorini, earlier (and sometimes still) known as Thera or Fira, is the most well known Greek island after Mykonos. The volcanic explosion of the mid-second millennium BCE, when the island was already inhabited, was one of the most powerful the world has known, destroying a large portion of the island and sending tidal waves well over parts of Crete. Today, the island’s landscape is wildly dramatic as a result, its architecture fairytale — and the entire bay an active volcanic crater. What might living on the tip of an active volcano do to the psyche of an island people? –perhaps encourage one to live in/for the moment….

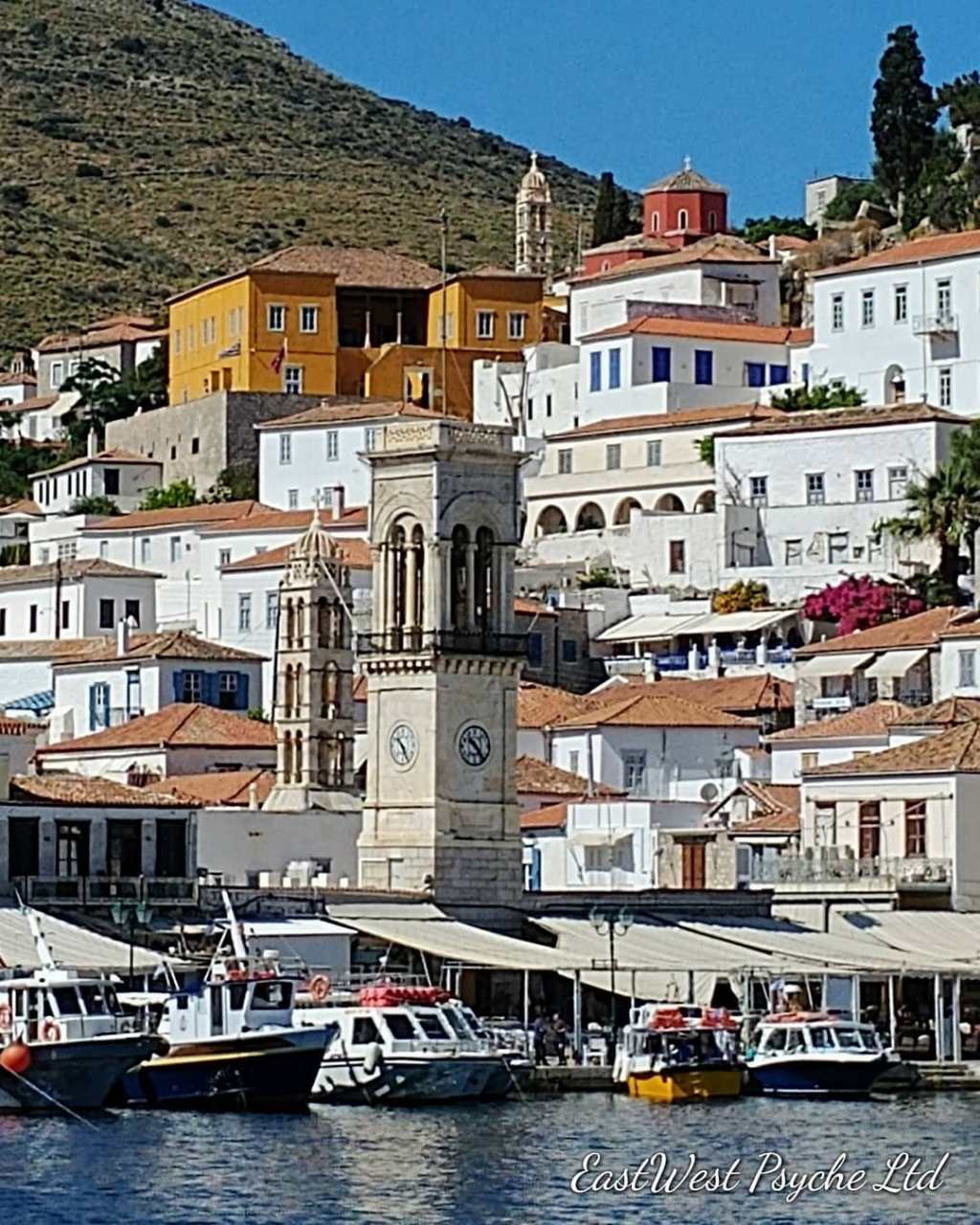

Hydra, near Athens in the Aegean Sea, was named for its historic natural springs. An easy and charming day trip, the island has had an important place in the country’s history, training ship captains and serving as a naval base in the nation’s war of independence in early 19th century. Before and for awhile after this period, the island was also known for its sponge diving. A possession of the Venetians from 12th to mid-16th centuries, it was then ruled by the Ottomans until 1821. As a location for new settlers, Hydra’s society became well accustomed to the integration of strangers.

Greek island life [pictured: Hydra] shares certain features with small villages in the country’s mountainous regions: isolation from other communities, a need for self-reliance as a result, a strong family unit, and a life that cycles around nature and the seasons — as well as the Orthodox Church.

Though not an island, the region of Halkidiki to the east of Thessaloniki in the north provides yet another sub-culture of Greece. With its mainland area housing 2 large lakes, the Bulgarian border just to the north and Turkey not far to the east, and its 3 narrow peninsulas with their rugged terrain that embraces both coastal and mountain life — as well as a healthy tourism industry, the result is a unique hybrid culture.

~EWP